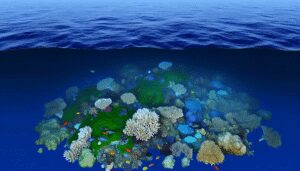

What must we sustain? Answers to that question are sometimes divided into “strong” and “weak” approaches. “Strong sustainability” gives priority to the preservation of ecological goods, like the existence of species or the functioning of particular ecosystems.

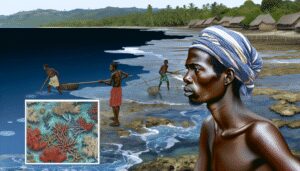

A “weak sustainability” disregards specific obligations to sustain any particular good, espousing only a general principle to leave future generations no worse off than we are. In terms of protecting old-growth forests, for example, a strong view might argue for protection, even if it requires foregoing development that would increase opportunities for future generations. A weak view would take into account the various benefits old-growth forests provide, and would then attempt to measure the future value of those benefits against the values created by development.

The two views loosely correspond to ecocentric (ecologically centered) and anthropocentric (human-centered) positions in environmental ethics, but not perfectly.

The ecocentric view requires that moral decisions take into account the good of ecological integrity for its own sake, as opposed to exclusively considering human interests. But a strong sustainability view could be held from an anthropocentric perspective by arguing that human systems depend on rich biodiversity or that human dignity requires access to natural beauty. Note also that a weak view would not necessarily approve the expiration of natural resources, even with the prospect of lucrative profit. For insofar as opportunities for future generations depend on certain ecological processes (e.g., breathable atmosphere), some ecological goods will always be more valuable than the economic development they make possible.

The ecocentric view requires that moral decisions take into account the good of ecological integrity for its own sake, as opposed to exclusively considering human interests. But a strong sustainability view could be held from an anthropocentric perspective by arguing that human systems depend on rich biodiversity or that human dignity requires access to natural beauty. Note also that a weak view would not necessarily approve the expiration of natural resources, even with the prospect of lucrative profit. For insofar as opportunities for future generations depend on certain ecological processes (e.g., breathable atmosphere), some ecological goods will always be more valuable than the economic development they make possible.

There is a third approach: A pragmatic middle view holds that, while we may not have obligations to sustain any particular nonhuman form of life or ecological process (the strong view), neither should we assume that all future opportunities can be measured against one another (the weak view). Th e moral and political philosopher Brian Barry (1997) argues that the preservation of some opportunities for future generations requires the enduring existence of particular ecological goods. For example, the opportunity to decide whether or not old-growth forests are required for a decent human life depends on their preserved existence. Th is approach effectively proposes that we must sustain conditions for the ongoing debate over sustainability. In another pragmatic approach, the philosopher Hans Jonas has proposed that new powers of human agency, able to comprehensively threaten their own conditions, require a new moral imperative to act responsibly for the sake of human survival. Perhaps sustainability is neither a strong question about nature’s intrinsic value nor a weak one about producing opportunities but rather a pragmatic question about keeping our species in existence (Jonas 1984).

Sustainability is then a question about maintaining a decent survival. Critics will object to such pragmatic approaches from two angles. On one hand, they look too humanistic: Neither old-growth forests nor threats to the survival of polar bears are priorities of the pragmatic view. On the other hand, they look insufficiently humanistic: reducing sustainability to the survival of the species may multiply inequality and ongoing poverty. A pragmatist could respond that, if the priorities of sustainability depend on a debate over what sustains us, then the argument could certainly be made that old-growth forests and the existence of polar bears sustain the human spirit, as do socially just societies and flourishing neighbors. Perhaps, rightly conceived, a decent human survival simply includes biodiversity and the end of extreme poverty. Allowing the massive loss of species would close down that option for humanity, effectively ending the debate. By now it is evident that theories of sustainability have become too complex to organize with dualistic terms like “strong” and “weak” or “ecocentric” and “anthropocentric.” We might instead think in terms of models for sustainability, each prioritizing its own component of what must be sustained. These models—economic, ecological, and political—are not mutually exclusive and often integrate complementary strengths of the others. Distinguishing them, however, helps make sense of alternative concepts of sustainability.

Sustainable Development Views and Paradigms Videos:

Sustainable Development Paradigms In-Depth:

– Sustainability Theory (PDF)

– A contested paradigm (PDF)

– Weak versus strong sustainability: exploring the limits of two opposing paradigms